Soviet Prison Tattoos : A Hidden History | Atlanta Tattoo Shop | Gate City Tattoo

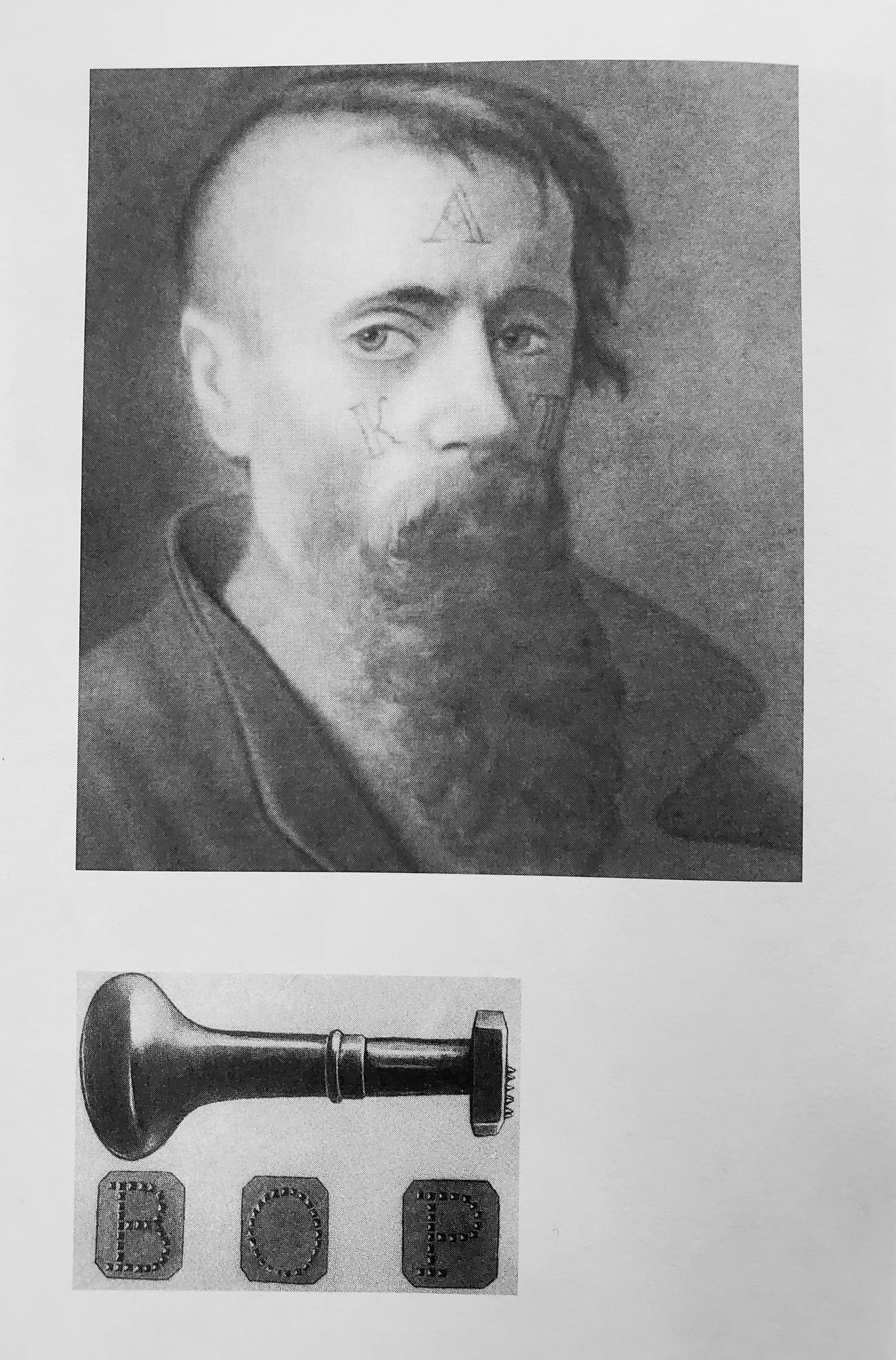

Russian Prison Tattoos initially got their start in the 19th century in Czarist Russia. Prisoners were branded with a spiked implement, and ink was rubbed into the wound resulting in a permanent tattoo. Typically the letters "KAT" (condemned) or “BOP” (thief) were imprinted on the face or other highly visible parts of the body to warn civilians of the wearer’s criminal history.

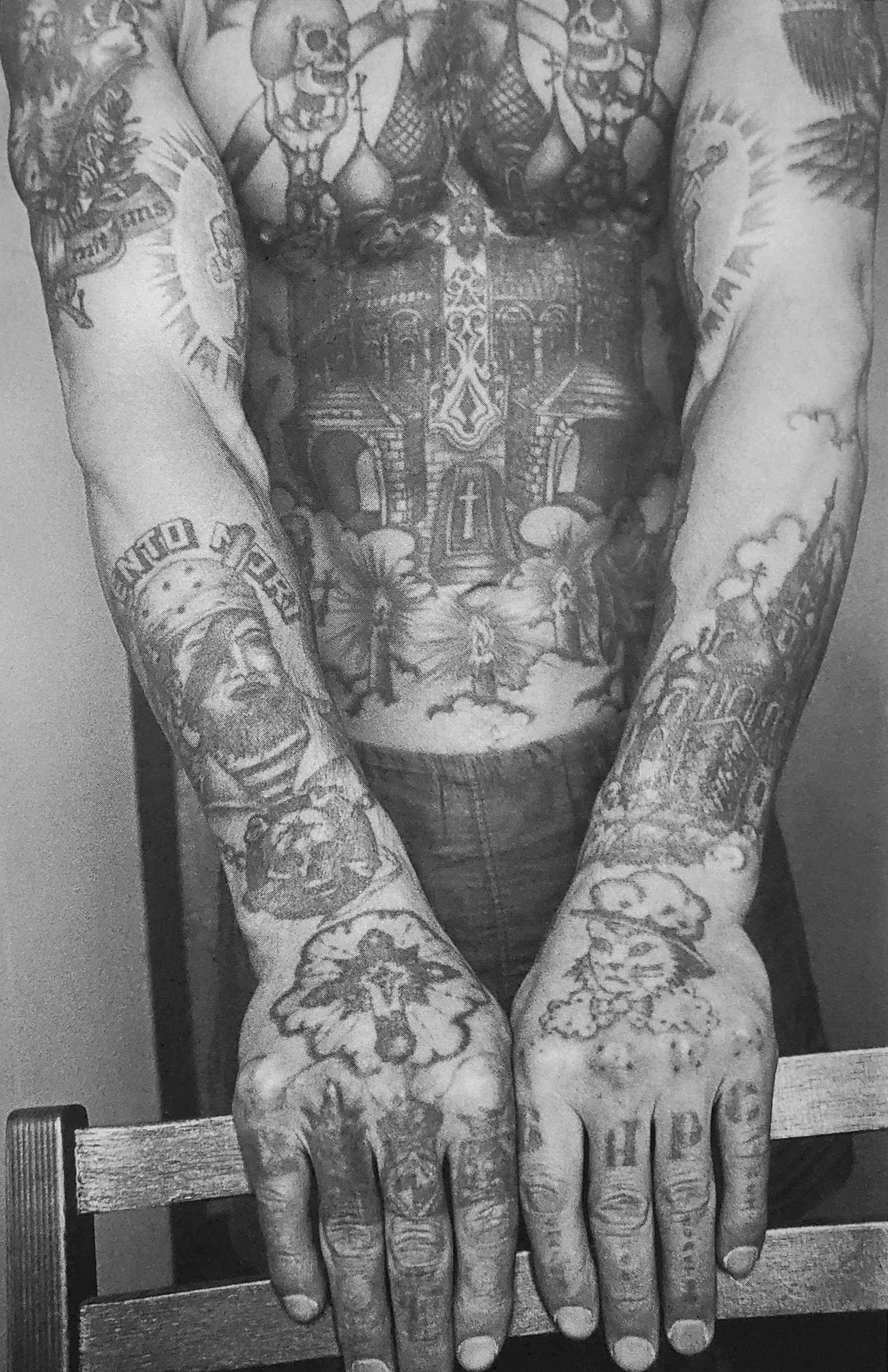

Despite this rudimentary beginning, tattooing in Soviet prisons soon developed into a sophisticated and complex language. Everything about a tattoo’s placement and imagery had significance in communicating the wearer's crime, length of sentence, social standing within the prison, etc. These images were law within the walls of these institutions and embodied the biography of the wearer. In the words of Danzig Baldaev "Tattoos embody a thief’s complete service record…They detail all of his achievements and failures, his promotions and demotions….Tattoos most often represent the language of the entire world of thieves, they are a means of socio-political communication”. These images were history, personal and political, etched into skin.

Tattoos in prisons were typically worn by convicts with status. During the intake process, inmates with tattoos were asked if their tattoos were a truthful reflection of their history. Convicts that couldn't stand by their tattoos were forced to remove the offending tattoos manually - such as through abrasion or chemical burns - to avoid the dire resolution of the issue by being solved by amputation or deathly beating. As Baldaev put it “Any deception here is considered blasphemy, a violation of the true sacred language”. Tattoos directly shaped the hierarchical structure within Soviet prisons and labor camps.

There are an abundance of articles covering the topic of Russian prison tattooing and the corresponding imagery in depth, so in this article I am going to focus on how historic events in the USSR impacted the trajectory of tattooing in prisons, and how tattoos chronicled these events transpiring under the Kremlin regime. Most of the information, along with all of the imagery used, has been pulled from Danzig Baldaev’s books on Russian Criminal Tattoos.

The prevalence and enforcement of prison tattoo culture is directly tied to the ebb and flow of the prison population, particularly repression of minorities under Stalin between the 1920s and 1950s. There is a fraught history of purges and ethnic cleansing responsible for the early buildup of the prison population: massacres during the 1920s, famine during the 1930s, political and ideological imprisonment in the 1940s. People were incarcerated or sent to labor camps as a result of defiance throughout these shifts in power. Many convicts have tattoos documenting these events and tattoos affirming their heritage, serving as talismans of protection in the aftermath.

With the population cumulatively building up since the inception of the USSR, the prison population exploded after the second World War. Overcrowded and subjected to hard labor, there was very little comfort to go around. Any of that went exclusively to those with ruling power within the law of the prison: established, tattooed convicts. Because of this all prisoners with tattoos were under heavy scrutiny and imposters were weeded out. The height of enforcement happened during this period, with prisoners violently punishing and murdering each other to affirm their power. This phenomenon was dubbed “The Bitches War”.

In an additional bid to combat overcrowding, legislators granted lighter sentencing to murders committed within the confines of prison by repealing an existing law that granted harsh sentencing in February of 1948. Prisoners in for 25 years or more would have only a few months added for any murders committed in prison, and this essentially provided a means of thinning out the prison population and granting even more legitimacy to "convicts law".

The severity of enforcement would continue to wax and wane after the 1940s, but by the mid 1970s tattoos faded from the forefront of structuring life and their sanctity faded. Conditions still remained horrific, however after the death of Stalin and throughout the weakening of the totalitarian regime, being a visibly non-conforming member of society became less taboo. Legitimacy was so much harder to regulate as petty criminals became well-versed in the cryptic language of prison tattoos. This coupled with the sheer amount of people in the USSR that had gone through the penal system had diluted the culture of criminality, as the line between a hardened criminal and an average citizen with an opinion became increasingly blurred (some sources estimate that about 1 in 5 citizens of the USSR had been to prison during this timeframe).

Citizens of Soviet states were severely punished for any sort of dissent or cultural expression (including speaking their own languages or practicing religion of any sort). Within the Soviet Union, ethnic and racial minorities were the targets of famine and genocide. Mass executions and incarceration of minorities kicked off in the 1920s, during the start of collectivization. In 1929 there was a massive uprising of Mongol-Buryat people who did not want their nomadic herds to become government property. As a result around 35,000 people were massacred and thousands sent to Gulags.

Baldaev documented tattoos on some of these Buryat inmates, good luck charms.

In the 1930s people in many Soviet territories - particularly Eastern Ukraine, Southern Russia and Northern Kazakhstan were subject to famine created by artificial scarcity, where all farm products were exported abroad and local populations were starved as an act of ethnic cleansing. Anywhere between 7-11 million people died as a result of this, a figure that is difficult to verify exactly as records were purposefully falsified to downplay these events. In 1932 Stalin passed a law where it became legal to execute or imprison a person stealing “stalks of wheat” or any form of food from the collective farms where they were working. Entire villages and towns were wiped out or imprisoned, and re-settled by Russian natives as a form of assimilation and erasure.

A tattoo worn by a Ukrainian convict born in prison to a mother jailed under the “stalks of wheat” law, lamenting the fate of both him and his mother. A Kazakh tattoo serving as a good luck charm.

Certain cases took this to the extreme, and entire cultural populations were interned in prisons and labor camps, as the very fact of their existence was problematic in the eyes of the regime. Notably, the Mongol-Kalmyk population was subject to mass incarceration, as on December 28, 1943 the entire population (nearly 200,000 people) was forcibly relocated and distributed among prison camps. It is estimated that 97-98,000 of them perished under horrific conditions.

A Kalmyk tattoo praying for the destruction of the Kremlin.

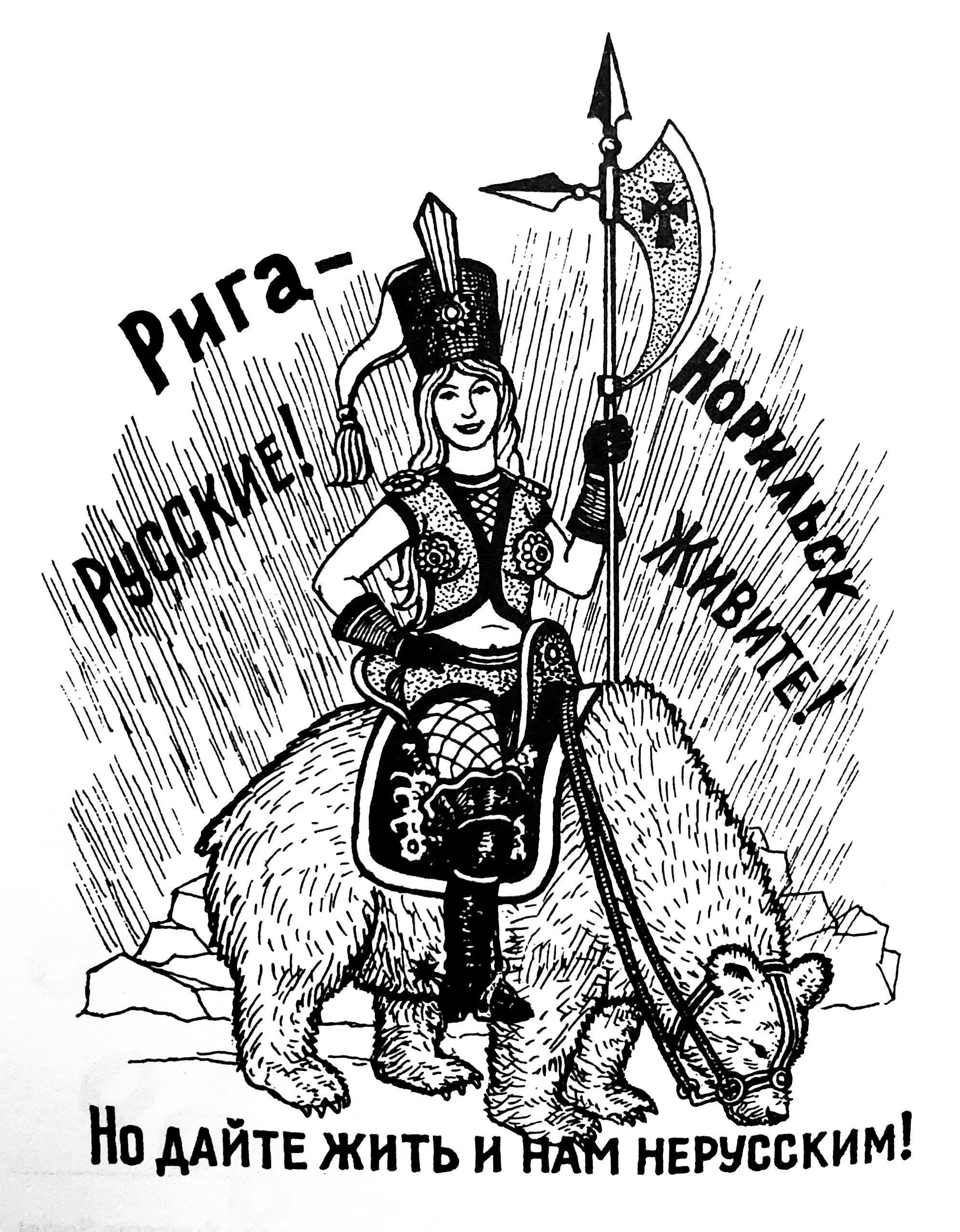

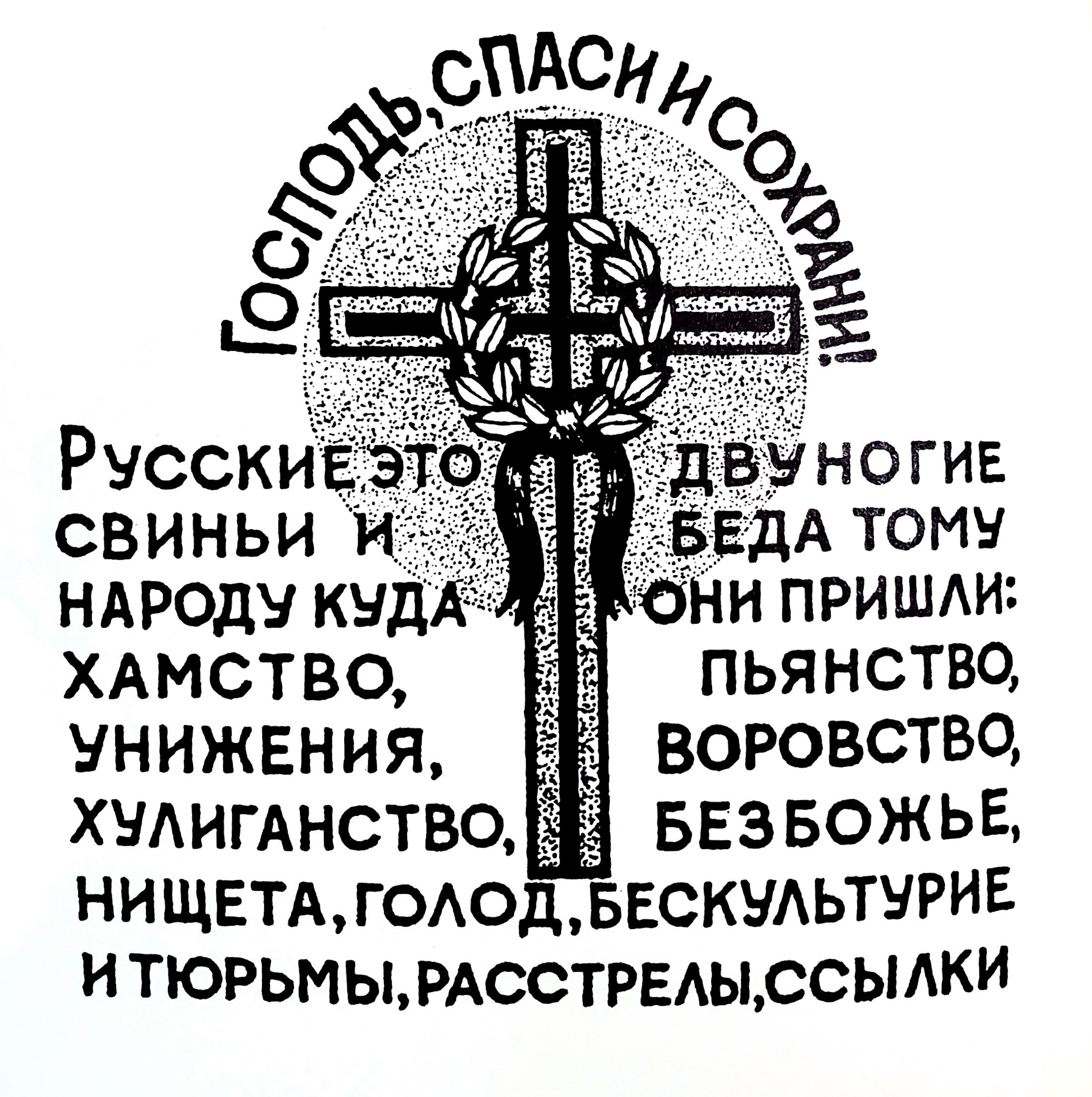

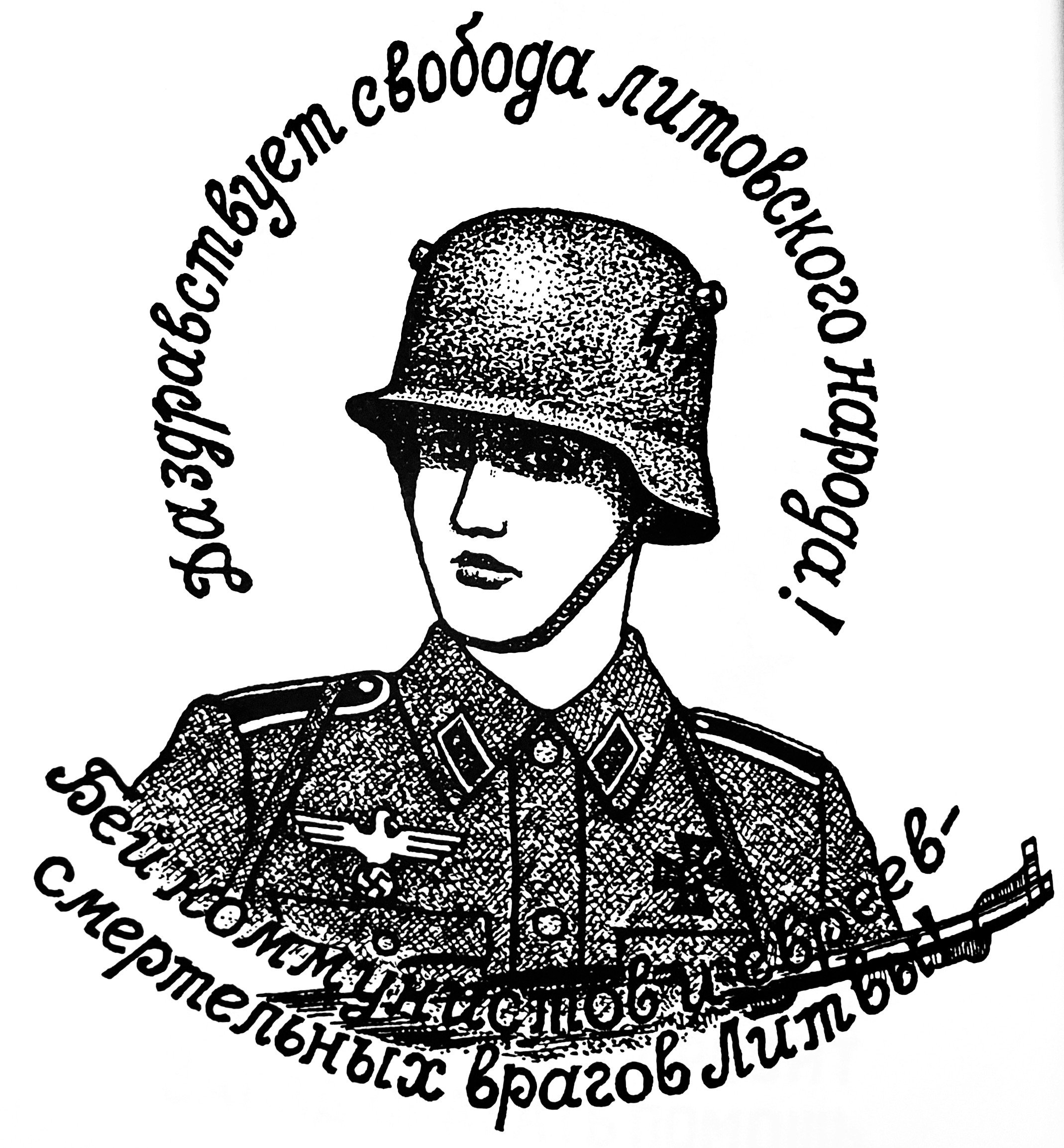

During the 1940s there was an additional mass incarceration of Baltic people, a direct result of the 1940 annexation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Anybody who resisted was executed on the spot, and whoever dissented was put behind bars. There are many nationalist or politically dissident tattoos on people of Baltic origin made during this time period, some calling for violence against the Kremlin and Russian people.

A cheeky anti-Russian tattoo on a Lithuanian woman. A tattoo placing a curse Russians. A militant, anti-government tattoo on a Lithuanian man.

These are just a handful of tattoos on prisoners interned as a result of repression and genocide, a reflection of only a few of the events that directly shaped the population of prisons in the USSR. Within a regime where cultural expression was controversial, these tattoos were insignia of survival, of triumph over the very state trying to destroy people’s heritage and individuality. Whether the imagery was vengeful, hopeful, humorous, or mournful it showed a refusal to back down, defiant resolve strengthened through the ritual of being tattooed on skin.

Written by Kristen Yurkevitch